Creative Writing Systems for Esperanto

The problem with an obsessive compulsion to be clean is that the shower is a dangerous source of ideas, and I can't in good faith claim that all of them are sensible.

This may be one of the silly ones, but it struck at the perfect moment. I had just decided to take a little social media hiatus. The combination was unbeatable. An impressive collab between shower and brain. I stood no chance.

So welcome inside my brain. Enjoy the ride while I recount the series of rabbit holes a small wet room subjected me to.

Now if you've read this blog before you'll be aware, perhaps painfully so, that I'm of the opinion that Zamenhof had a keen eye for language (he was an ophthalmologist – stay with me) and produced a masterpiece in Esperanto.

Esperanto is written using the latin script, but on the occasion in question, the shower gave me cause to question whether it should be.

This little adventure was by no means intended to produce a viable proposal for a new Esperanto writing system. Instead I intended only to indulge myself and demonstrate in the clearest manner possible that I do in fact have too much free time.

As I flipped around the “closed” sign on the inside of the door of my brain to this wacky idea, entered first Phoenician, boasting proudly of its ancient and beautiful letters.

Phoenician is the ancestor of the Greek alphabet and, hence, of all Western alphabets. In fact an abjad (vowels aren't written and must be inferred by the reader) rather than an alphabet, Phoenician was written from the 11th century BC and from right-to-left.

I like the way the Phoenician letters look, so I wanted to experiment with something resembling the Phoenician script.

The first step in my adventure was to map the Phoenician letters (consonants) to their closest Esperanto equivalents:

| a | b | c | ĉ | d | e | f | g | ĝ | h | ĥ | i | j | ĵ |

| - | 𐤁 | 𐤑 | - | 𐤃 | - | - | 𐤂 | - | 𐤄 | 𐤇 | - | 𐤉 | - |

| k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | ŝ | t | u | ŭ | v | z |

| 𐤊 | 𐤋 | 𐤌 | 𐤍 | - | 𐤐 | 𐤓 | 𐤎 | 𐤔 | 𐤕 | - | - | - | 𐤆 |

Of course I still owe you an A, E, I, O and a U, plus a few extra Esperanto characters.

Luckily, Phoenician and its close friend Aramaic still had a few extra letters to donate to the cause.

Here's the result:

| a | b | c | ĉ | d | e | f | g | ĝ | h | ĥ | i | j | ĵ |

| 𐤀 | 𐤁 | 𐤑 | 𐡂 | 𐤃 | 𐤈 | ࠅ | 𐤂 | 𐡍 | 𐤄 | 𐤇 | 𐡆 | 𐤉 | 𐤙 |

| k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | ŝ | t | u | ŭ | v | z |

| 𐤊 | 𐤋 | 𐤌 | 𐤍 | 𐤏 | 𐤐 | 𐤓 | 𐤎 | 𐤔 | 𐤕 | 𐤒 | ࠒ | 𐡉 | 𐤆 |

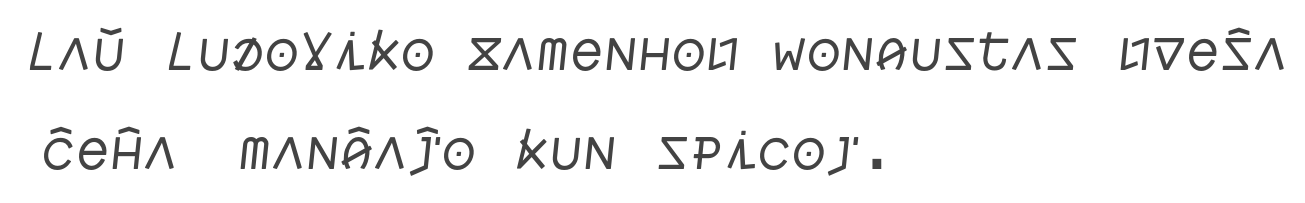

And here's what it looks like:

Hello, I'm called Martin

Saluton, mi nomiĝas Martin

𐤍𐤏𐤕𐤒𐤋𐤀𐤎, 𐡆𐤌 𐤎𐤀𐡍𐡆𐤌𐤏𐤍 𐤍𐡆𐤕𐤓𐤀𐤌

Echo change every Thursday

Eĥoŝanĝo ĉiuĵaŭde

𐤏𐡍𐤍𐤀𐤔𐤏𐤇𐤈 𐤈𐤃ࠒ𐤀𐤙𐤒𐡆𐡂

PS: if you're wondering why anybody who could reasonably claim sanity needs to say "echo change every Thursday", don't worry, that's a totally reasonable doubt to have.

In Esperanto culture, we like to make sure that the way words echo changes roughly once per week, and historically we all get together on Thursdays to figure out which echo we'd like to have for the coming week.

Rather helpfully, it's also a good example of a phrase that uses all the the Esperanto accented letters at the same time. That's just a totally random coincidence, of course.

Anyway, it'd be cool if we could play with some custom sentences and magically see what they look like in this new Phoenician-inpired alphabet.

Old-school witchcraft used big old cauldrons with handfuls of newt eyes and the toes of frogs, but it's mostly done with JavaScript these days. And so with absolutely no impact on the jumping distance of nearby frogs, or the sight of newts, you can now play around with this new alphabet:

A little after the early Greek alphabet emerged from Phoenician, other regional scripts emerged from that.

In what today is Bodrum, Turkey, the Carians (11th – 6th century BC) spoke their native Carian and wrote in a cool-looking script.

Using the Carian script (the Kaunos variant) as inspiration for round two, here's an approximation of Carian's letters mapped to Esperanto's sounds.

| a | b | c | ĉ | d | e | f | g | ĝ | h | ĥ | i | j | ĵ |

| 𐋎 | Γ | 𐊡 | 𐊭 | 𐊢 | 𐊺 | 𐋄 | Λ | 𐊬 | 𐋏 | Θ | 𐊹 | 𐊑 | 𐊨 |

| k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | ŝ | t | u | ŭ | v | z |

| 𐊼 | 𐊣 | 𐊪 | 𐊵 | 𐊫 | 𐊷 | 𐊥 | 𐊰 | 𐊯 | 𐌓 | 𐊲 | 𐊾 | 𐊴 | 𐊳 |

As with the Phoenician approach, I had to add custom characters to fill some gaps where there was no close mapping between the Carian and Esperanto sound.

Let's see what this looks like:

Hello, I'm called Martin

Saluton, mi nomiĝas Martin

𐊰𐋎𐊣𐊲𐌓𐊫𐊵, 𐊪𐊹 𐊵𐊫𐊪𐊹𐊬𐋎𐊰 𐊪𐋎𐊥𐌓𐊹𐊵

Echo change every Thursday

Eĥoŝanĝo ĉiuĵaŭde

𐊺Θ𐊫𐊯𐋎𐊵𐊬𐊫 𐊭𐊹𐊲𐊨𐋎𐊾𐊢𐊺

In some way this definitely feels more Greek-inspired, but I was curious whether it would look better if the letters occupied different spots so they more closely mapped to the forms of the Esperanto letters. For instance, the Carian letter "𐊰" creates the sound /s/ and "𐌓" /t/.

After the great rearrangement, I ended up with this variant:

| a | b | c | ĉ | d | e | f | g | ĝ | h | ĥ | i | j | ĵ |

| 𐋎 | 𐊡 | 𐊢 | 𐊾 | 𐊹 | 𐊺 | 𐊥 | 𐊬 | Λ | 𐋏 | Θ | 𐊑 | 𐊵 | 𐊨 |

| k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | ŝ | t | u | ŭ | v | z |

| 𐊣 | 𐊼 | 𐊰 | 𐊪 | 𐊫 | 𐌓 | Γ | 𐊴 | 𐋄 | 𐊷 | 𐊲 | 𐊯 | 𐊭 | 𐊳 |

And instead we have:

Hello, I'm called Martin

Saluton, mi nomiĝas Martin

𐊴𐋎𐊼𐊲𐊷𐊫𐊪, 𐊰𐊑 𐊪𐊫𐊰𐊑Λ𐋎𐊴 𐊰𐋎Γ𐊷𐊑𐊪

Echo change every Thursday

Eĥoŝanĝo ĉiuĵaŭde

𐊺Θ𐊫𐋄𐋎𐊪Λ𐊫 𐊾𐊑𐊲𐊨𐋎𐊯𐊹𐊺

Now that some of the letters have similar forms to their Esperanto counterparts, some of this script has become more recognisable. For example, "𐊰𐊑" and "𐊪𐊫𐊰-".

Damn. Now I'm hungry.

Here's a Carian-inspired input for you to play with yourself:

Now yes, Phoenician and Carian are cool parents. They give me what I need, they don't bug me much, but what if I just left home and went my own way?

Take 3.

This time I wanted to cherry-pick the letters myself based entirely on their forms, aiming to build up a complete set that look good together. Like a 28 member boyband.

Taking inspiration from basically everything (thanks, Unicode), the third incarnation of what started as an innocent attempt to clean myself has now become the following:

| a | b | c | ĉ | d | e | f | g | ĝ | h | ĥ | i | j | ĵ |

| ა | ᯖ | c | ċ | မ | ᨧ | σ | г | ґ | h | ħ | ⲓ | 𑀯 | 𑀙 |

| k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | ŝ | t | u | ŭ | v | z |

| ꮵ | 𑣜 | 𐳆 | 𐳝 | ɵ | 𐐸 | ɾ | ᨣ | ᩆ | 𐳇 | ᦢ | ᨾ | ꮑ | ᰣ |

While I wanted the letters to have unique forms so that the overall alphabet felt unique, I also made sure related letters such as "c" + "ĉ", "g" + "ĝ", "j" + "ĵ", "s" + "ŝ" and "u" and "ŭ" felt like peas in a pod.

Let's see how this one looks:

Hello, I'm called Martin

Saluton, mi nomiĝas Martin

ᨣა𑣜ᦢ𐳇ɵ𐳝, 𐳆ⲓ 𐳝ɵ𐳆ⲓґაᨣ 𐳆აɾ𐳇ⲓ𐳝

Echo change every Thursday

Eĥoŝanĝo ĉiuĵaŭde

ᨧħɵᩆა𐳝ґɵ ċⲓᦢ𑀙აᨾမэᨧ

And it'd be unfair of me not to throw in a few extra frog's toes. So please, go wild:

You'd think this would be enough.

You'd think I would've had something more important to do, a friend to meet, just anything that might've led to the conclusion that this is enough. "You've explored your intellectual curiosity Martin! You've honoured the sanctity of the shower thought! Go to bed. Sleep. Sleep is good."

As you can discern either from my tone of voice or the size of the scroll bar, this in fact did not happen.

The great thing about silly ideas is that they breed. So, full steam ahead.

Next up: adjabs.

An adjab, or "consonantary" if you wish to sound posh my good fellow, is an early writing system used by people so lazy that they didn't even bother to include the vowels.

Several are still used today, such as Arabic and Hebrew. While reading these languages, or any adjab, your mouth fulfils its oratorial destiny only by way of your brain filling in the blank vowels for you as you read.

The nice property of an adjab is that, without vowels, the written language feels shorter and more compact. Well, it literally is shorter, and I mean literally in the literal sense of the word.

Esperanto as an adjab is just Esperanto with no vowels:

| - | b | c | ĉ | d | - | f | g | ĝ | h | ĥ | - | j | ĵ |

| k | l | m | n | - | p | r | s | ŝ | t | - | ŭ | v | z |

That table was completely unnecessary. On the other hand, if you were avoiding asking what vowels were, well now you know for sure.

We then end up with something like:

Hello, I'm called Martin

Saluton, mi nomiĝas Martin

Sltn, m nmĝs Mrtn

Echo change every Thursday

Eĥoŝanĝo ĉiuĵaŭde

ĥŝnĝ ĉĵŭd

I already ate so I am neither eating nor will eat

Mi jam manĝis do mi nek manĝas nek manĝos

M jm mnĝs d m nk mnĝs nk mnĝs

Clearly this is a non-starter. If we lose the vowel we have no idea whether verbs ending –s are referring to past (–is), present (–as), future (–os) or conditional (–us). It'd be too much work for the reader to figure this out while reading.

On the other hand, we do read using patterns. If you take out several letters of a long sentence in most languages, people can usually still read the sentence perfectly well. Humans are really good at error correction. Well, other people's errors – I don't make errors personally.

Shifting gears, what if we dropped the middle of words, but only when it didn't leave some difficult ambiguity to resolve.

What would that probable atrocity look like?

Hello, I'm called Martin

Saluton, mi nomiĝas Martin

Saon, mi noas Martin

Echo change every Thursday

Eĥoŝanĝo ĉiuĵaŭde

Eĥĝo ĉide

I already ate so I am neither eating nor will eat

Mi jam manĝis do mi nek manĝas nek manĝos

Mi jm mais do mi nk maas nk maos

The echo change ritual has been completely destroyed, but it kind of works with the other examples. However, there's stil a huge burden on the reader to figure out what's missing while they're reading.

I like it about as much as I like pineapple on pizza.

Enter diacritics.

Diacritics are the little lines, dots and squiggles written above or below letters. They're designed to compliment a letter and give us more information about it.

Esperanto indicates the grammatical function of many kinds of words in the way the word ends. In theory these could be replaced with some kind of accent to compress the written language and produce a new script at the same time.

After a few rounds of trying I came up with the following:

For verbs:

| Example | Unicode | Position | |

| –i | X̩ | 0329 | S1 |

| –is | X̖ | 0316 | S1 |

| –as | X̱ | 0331 | S1 |

| –os | X̗ | 0317 | S1 |

| –u | X̣ | 0323 | S1 |

| –us | X̰ | 0330 | S1 |

And for everything else:

| Diacritic | Unicode | Position | |

| Adverbs | X̱ | 0331 | E1 |

| Nouns | X̥ | 0325 | S1 |

| Adjectives | X͚ | 035A | S1 |

| Singular | X̩ | 0329 | S2 |

| Plural | X͈ | 0348 | S2 |

| Object | X̣ | 0348 | S3 or E3 |

Now I know this looks complicated. I was just spiralling at this point. Cut me some slack.

I selected 6 diacritics for the 6 different verb endings. I tried to choose marks that had some sort of logic. Present tense is a single horizontal line to indicate moving forward in time, whereas future tense is a mark that moves up and to the right.

My use of "S" and "E" (in the position column) indicates whether the diacritic should be placed at the start or end of the word. The numbers indicate how the diacritic should be stacked when several diacritics are used together. It's possible to have a plural, accusative adjective, y'know?

Focusing on verbs first, let's take a look at some examples of this system:

I would like to have

Mi ŝatus havi

Mi ŝ̰at h̩av

I will arrive early

Mi alvenos frue

Mi a̗lven frue

I want you to stay

Mi volas ke vi restu

Mi v̱ol ke vi ṛest

Listen, I don't hate it.

What about adverbs?

Beautifully

Bele

Beḻ

Wondefully

Mirinde

Mirinḏ

To the north

Norden

Norḏ̣

Notice how for "norden" (to the north), I've stacked the adverb ending with the object ending. How about when we stack more diacritics?

Box

Skatolo

S̥̩katol

Big boxes

Grandaj skatoloj

G͚͈rand s̥͈katol

Big boxes (object)

Grandajn skatolojn

G͚͈̣rand s̥͈̣katol

I would really like to have beautiful sweet cookies to eat

Mi tre ŝatus havi belajn dolĉajn kuketojn por manĝi

Mi tṟ ŝ̰at h̩av b͚͈̣el d͚͈̣olĉ k̥͈̣uket por m̩anĝ

There's a reduction in the horizontal length of sentences, but at the cost of some vertical space. The primary issue I have with this system is the fact I'm seeing ice-cream cones everywhere and it's making me hungry again.

It looks cool though, and it's nice that no information is lost in this encoding.

It's almost deceptive the fact that Esperanto encodes so much grammatical information in the way words start and end. However, it's also true that most of those encodings are made up of vowels. Adjectives end with "e", verbs with "i", "o", "a" etc., nouns with "o".

Maybe there's some more life in the old adjab + diacritics path, but simply using the diacritics to mark the missing vowels. Then we'd have something similarly compressed horizontally, but much easier to use.

What if we used the missing vowels themselves as superscript diacritics?

| Vowel | a | e | i | o | u |

| Diacritic | Xͣ | Xͤ | Xͥ | Xͦ | Xͧ |

| Unicode | 0363 | 0364 | 0365 | 0366 | 0367 |

Let's see how this looks:

I would really like to have beautiful sweet cookies to eat

Mi tre ŝatus havi belajn dolĉajn kuketojn por manĝi

mͥ trͤ ŝͣtͧs hͣvͥ bͤlͣjn dͦlĉͣjn kͧkͤtͦjn pͦr mͣnĝͥ

Give me a second... I'm just looking through my thesaurus for a stronger version of "outrageous".

If there was ever a way to imagine what a sentence would look like drunk out its skull, I think this might be it. I think we can agree that nobody wants to read Esperanto like this.

But what if we used subscript diacritics instead, and ideally more subtle ones. Something reminiscent of Hebrew's "niqqud" system.

| Vowel | a | e | i | o | u |

| Diacritic | X̠ | X̤ | X̣ | X̥ | X͈ |

| Unicode | 0320 | 0324 | 0323 | 0325 | 0348 |

Let's see how this looks with a sentence that carries nothing but truth for me right now.

I would really like to have beautiful sweet cookies to eat

Mi tre ŝatus havi belajn dolĉajn kuketojn por manĝi

ṃ tr̤ ŝ̠t͈s h̠ṿ b̤l̠jn d̥lĉ̠jn k͈k̤t̥jn p̥r m̠nĝ̣

This looks more elegant with the vowel markings under the letters, and especially due to using non-letter diacritics.

I quite like this system. In fact, in the course of this shower-thought-turned-art-project I have almost come to be able to read it naturally.

Try it out with some of your own examples:

Shifting gears, I wanted to refocus on how a new writing system could simply be conventions around what not to write, rather than adding new letters or diacritics.

Initially I considered that Esperanto has six diphthongs: aj, aŭ, ej, eŭ, oj, uj. If they could be substituted for single-letter alternatives, perhaps that creates a nicely reduced written language.

But how often do they actually occur in modern Esperanto? Or an even better question: which are the most commonly occurring letter patterns?

As with any good question, the only way to answer it is with even more questions. The first of which was "where do I find lots of well-written Esperanto?"

I'm a big fan of the magazine Kontakto, which is published 6 times per year. It's a great example of how you can learn so many interesting things about the world via the Esperanto language. It almost always contains high-quality articles and discussions.

So, "Kontakto" was the answer, and "How?" the consequent question.

Conveniently, the UEA's website contains a free archive of every Kontakto edition for every year prior to the current one.

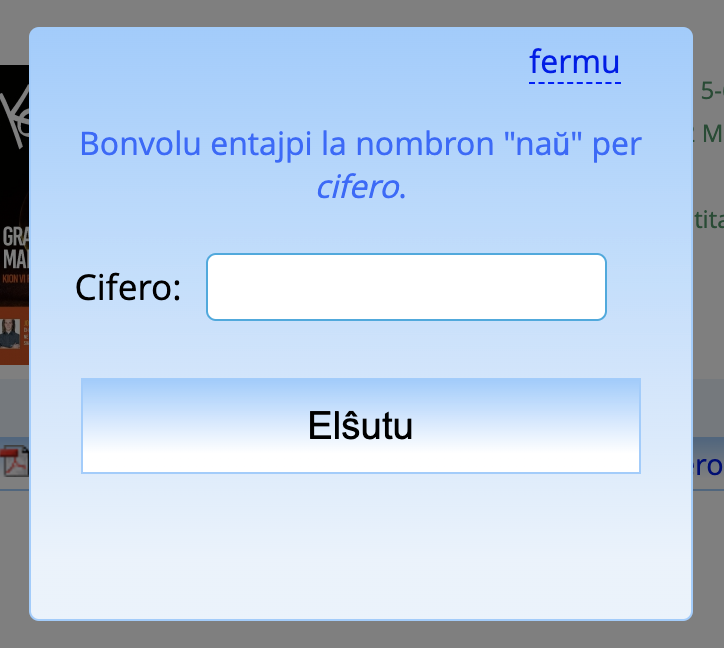

Inconveniently, when you request the link, you're greeted with an anti-bot challenge:

This asks: "Please type in the number nine as a digit." A random digit is chosen each time, naturally.

Everything would be great if the request to UEA's server didn't include both the answer and the question. Small pro-tip for ya, UEA: don't do that.

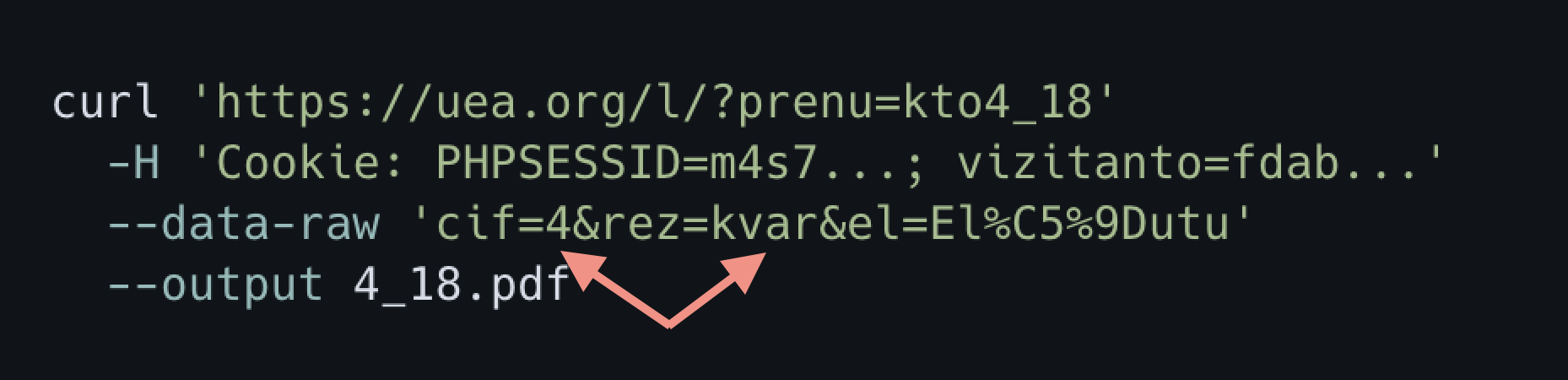

Why? Well because I can just supply my own question and answer each time and very easily bypass your anti-bot protection. And that's exactly what I did, naturally.

A quick curl command later and I had 5 years of Kontakto from 2022 to 2018.

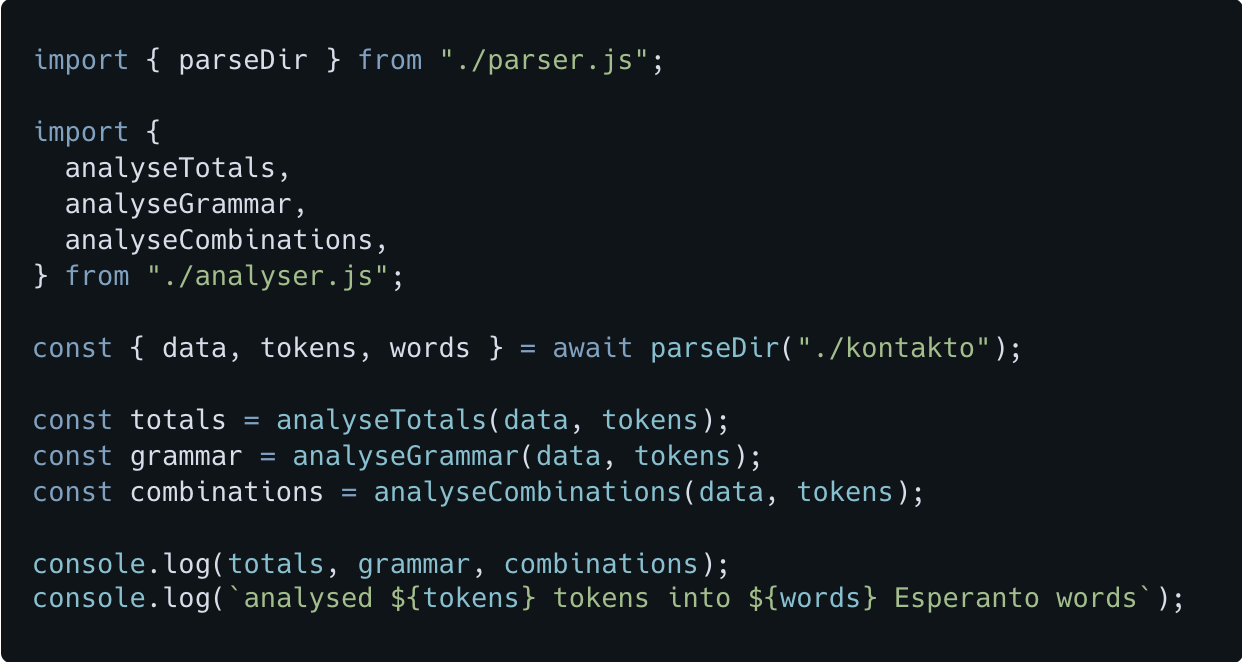

Next I wrote code to parse those documents, combine all the text and analyse how the language is used.

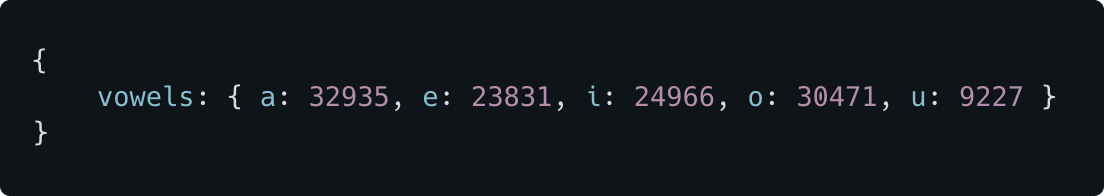

The dataset contained 320,714 words, which after processing constituted 35,743 unique Esperanto words.

"Rabbit hole" doesn't even cover it at this point.

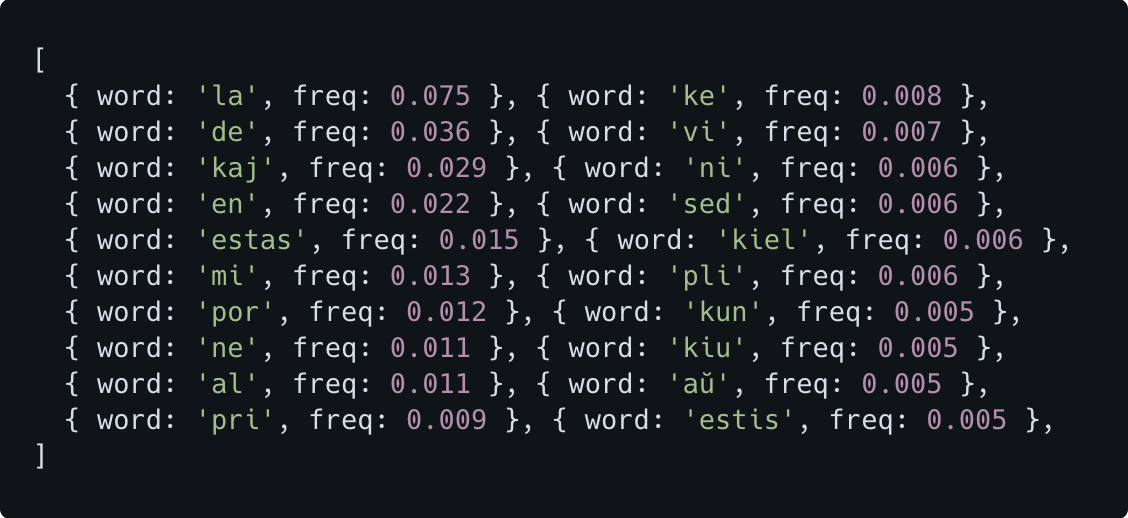

Let's see what the most common words were in my data:

The combination of la, de, kaj, en, mi, por, ne, al make up around 20% of the total words.

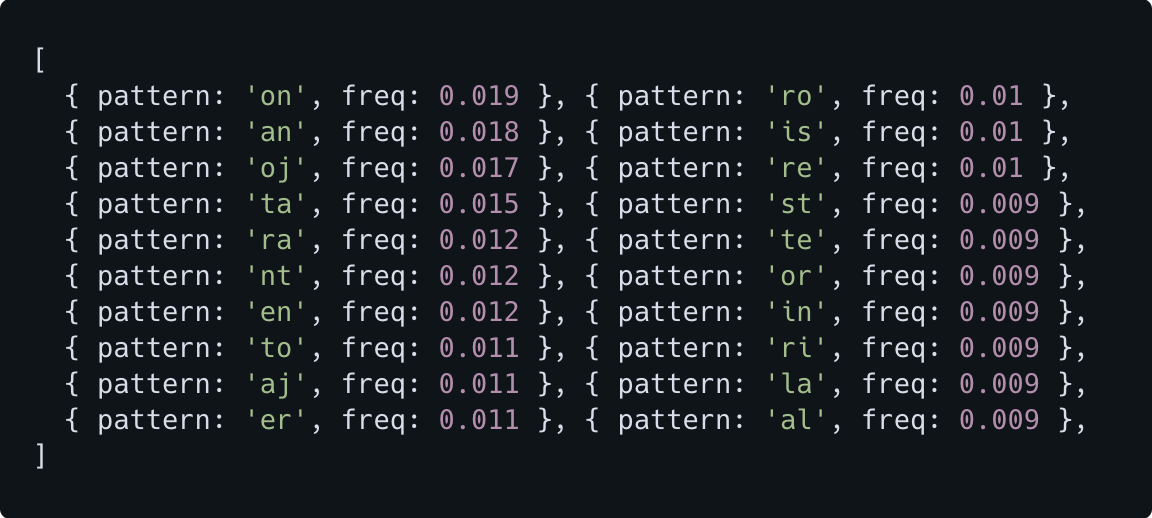

Of course these are full words and diphthongs occur within words. Next I analysed the most common two letter combinations within the data:

About as unsurprisingly as a the fact you no longer fit into your old jeans, the diphthongs oj and aj make an appearance, as well as on, an.

For the non-Esperanto speakers, that by some impressive combination of willpower and stubbornness made it this far, oj, aj, an, on are very common in Esperanto because it's how all adjectives and nouns end.

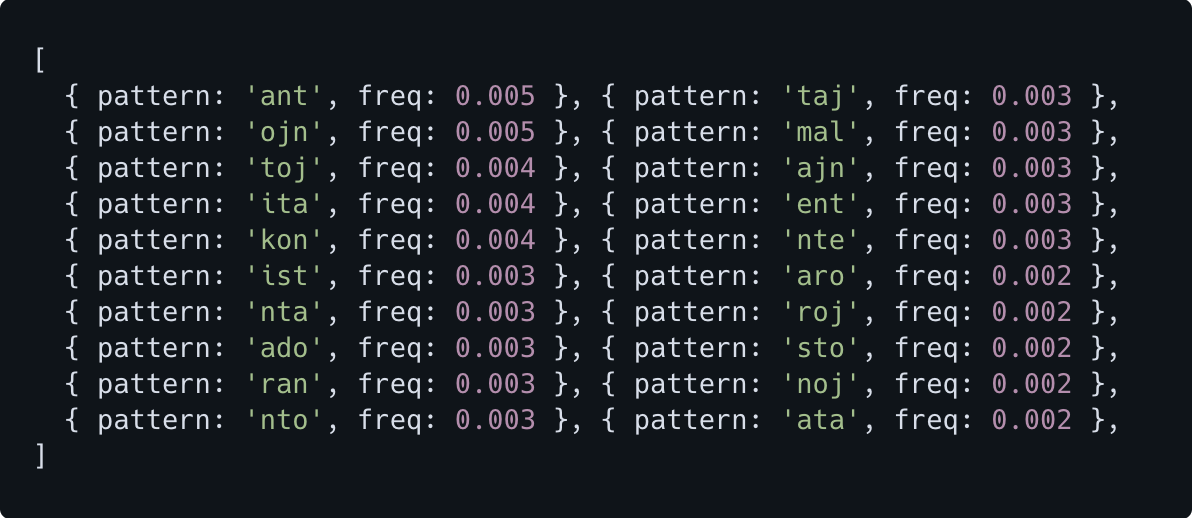

So what about three letter combinations?

We're down at 0.5% frequency for the most common 3-letter combination. The combinations ant, ojn, toj, ita, ist aren't too surprising as they occur in many Esperanto words.

The kon may be a result of context: certain words are used more often in a magazine, such as kontrol- (check), enkonduk- (introduce), rakont- (tell), kongres- (congress), etc. The word "Kontako" itself was excluded from the data.

The most common full words occur more often than the most common two-letter or three-letter intra-word combinations.

The next idea was to replace the most common full words with their single-letter equivalents. So l, d, k, e, m, p, n, a standing in for la, de, kaj, en, mi, por, ne, al.

Some Esperantists already do this by using k for kaj for example.

Let's see how that looks:

My friend goes to school in the morning to learn and I can't go with her

Amikino de mi iras al la lernejo en la mateno por lerni kaj mi ne povas iri kun ŝi

(82 characters)

My friend goes to school in the morning to learn and I can't go with her

Amikino d m iras a l lernejo e l mateno p lerni k m n povas iri kun ŝi

(70 characters)

Another route might be to find a convention around vowel usage that allows a vowel to be omitted. A naïve approach could be to assume a missing vowel is always an "i", but which is actually the most commonly occurring vowel?

OK, so let's go with "a":

mikino de mi irs l l lernejo en la mteno por lerni kj mi ne povs iri kun ŝi

(75 characters)

But now we're back to not knowing which conjugation was intended by "irs" and "povs".

The most common vowel in my data set isn't necessarily helpful in another context. Perhaps we could choose which vowel to drop based on the context, but only that vowel can then be dropped from other words.

Combined with the single-letter replacements for the top 8 words we end up with:

Amkno d m ras a l lernejo e l mateno p lern k m n povas r kun ŝ

(63 characters)

This system sort of works.

Once I see "ras" I can deduce that the vowel dropped must be an "i". I then mentally add that back in as I read the rest of the sentence. I know the "l" is "la" not "li" (he) because "l" is one of the top 8 words now being treated as a single letter replacement. Similarly "n" must be "ne" as apposed to "ni" (we).

However, there's a lot of cognitive overhead for a 25% character reduction, especially for the reader, who now has to work out which vowel was killed in the dining room with the candlestick.

Of the ideas I've explored here, I quite like the subscript diacritical adjab, and not only due to its catchy name. It has the nice properties of being shorter and looking more unique without overdoing it.

Esperanto is a cool language and you should learn it

Esperanto estas mojosa lingvo kaj vi devus lerni ĝin

Esp̤r̠nt̥ est̠s m̥j̥s̠ ḷngv̥ k̠j ṿ d̤v͈s l̤rṇ ĝ̣n

The downside would be writing it without a tool like the ones I've created in this article.

In the interest of this article not accidentally becoming a PhD, my little journey into creative alternative ways to write Esperanto ends here.

But before I leave you, I'm pleased to report that I'm not alone in my public demonstrations that I have far too much free time.

- Ernest L. Jackson has adapted the Gregg shorthand system for writing Esperanto.

-

Esperanto already has a braille alphabet.

a b c ĉ d e f g ĝ h ĥ i j ĵ ⠁ ⠃ ⠉ ⠩ ⠙ ⠑ ⠋ ⠛ ⠻ ⠓ ⠳ ⠊ ⠚ ⠺ k l m n o p r s ŝ t u ŭ v z ⠅ ⠇ ⠍ ⠝ ⠕ ⠏ ⠗ ⠎ ⠮ ⠞ ⠥ ⠬ ⠧ ⠵ -

There are additions to Morse code to capture the Esperanto characters:

ĉ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ĝ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ĥ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ĵ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ŝ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ŭ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ -

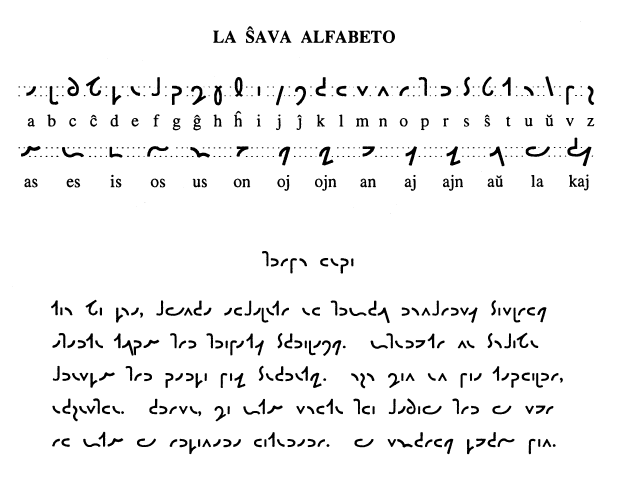

John Wesley Starling created the Ŝava alphabet to write Esperanto with a custom alphabet that also encodes gramatical endings and common words as specific ligatures.

-

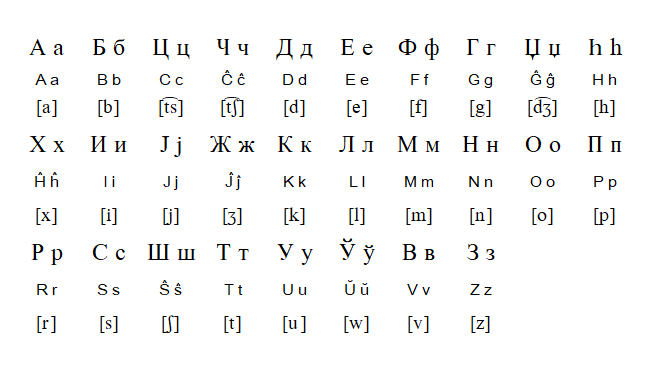

Esperantists in the soviet era didn't have typewriters with Latin letters, so they wrote Esperanto using the Cyrillic alphabet.

-

The 2017 Japanese-language visual novel The Expression Amrilato and its 2021 sequel Distant Memoraĵo feature a language named Juliamo which is actually Esperanto in a modified Latin alphabet.